Malnutrition in children

In the first years of life and throughout childhood, children undergo tremendous physical and mental development. A healthy lifestyle with access to sufficient nutritious food is essential. It sets the course for optimal growth, a strong immune system and a generally healthy and active life.

However, as global hunger is still one of the greatest challenges of our time, many children are affected by malnutrition and are therefore exposed to an increased risk of illness and death. Worldwide, around 45 million children under the age of five are considered wasted, meaning their weight is too low in relation to their height. Despite global progress in reducing the child mortality rate, one child or adolescent still died every 4.4 seconds in 2021 - a total of around five million children under the age of five. Malnutrition is a major factor in around half of these deaths.

A healthy and balanced diet, especially in the first 1,000 days of life (measured from the time of fertilization), is considered crucial for the course of the development. Without it, physical and mental development may be delayed. There is still a long way to go before all children have equal opportunities for a healthy start in life. We are therefore particularly committed to the prevention and treatment of malnutrition in children.

What does malnutrition in children mean?

The term malnutrition is used by experts as an overarching term for various forms of malnutrition and describes either a deficit, a surplus or an imbalance in energy and/or nutrient intake. The following table provides an overview of different forms and their definitions.

| Insufficient energy and/or nutrient intake | Excess energy and/or nutrient intake |

Undernutrition: This occurs when children do not consume enough food or nutrients. A distinction is made between different forms:

| Overweight: Excessive weight in relation to the child's height

|

In this context, the term "triple burden of malnutrition" is often used. In many countries and even within households, these three forms of malnutrition - undernutrition, hidden hunger and obesity - occur side by side. This means that a single country may face the challenge of tackling high rates of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and obesity. Or a family may have an overweight mother and an underdeveloped child. These trends reflect what is known as the triple burden of malnutrition, a burden that threatens the survival, growth and development of children, economies and societies.

Negative trend: Obesity among children continues to rise

The number of people with severe overweight (obesity) almost tripled between 1975 and 2016. In 2020, around 39 million children under the age of five were overweight or obese. This affects children growing up in countries of the Global South as well. In Africa, the number of overweight children rose by around 24 percent between 2020 and 2021. However, the global prevalence of obesity in children under the age of five has remained the same, barely changing from 5.5 percent (37 million) in 2012 to 5.6 percent (37 million) in 2022. The result of obesity is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer. Excessive fat accumulation is preventable through a healthy lifestyle.

Is the BMI suitable as an indicator for determining malnutrition?

The Body Mass Index (BMI) is an indicator of the nutritional status of adolescents and adults. The BMI is determined by a simple calculation: Body weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. With a BMI of 18.5 and lower, a person is considered undernourished. In theory, calculating the BMI is a very good way of diagnosing malnutrition. For children, however, the World Health Organization's standards for growth are more suitable for determining malnutrition and are used in practice. Here, so-called percentiles (scattering of a statistical distribution) can be used to make statements about the malnutrition of a child with little data. Especially in crisis situations, percentiles and the MUAC test can provide better information about the mortality risk of children.

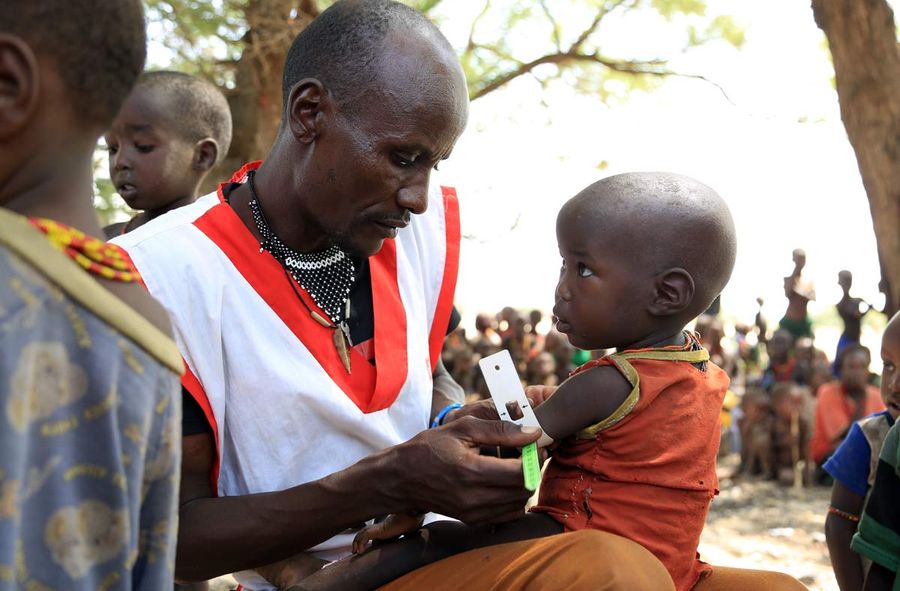

Diagnosis of malnutrition in children with the MUAC test

The MUAC test is a simple method widely used in humanitarian work to diagnose malnutrition, or more precisely: the level of wasting or acute malnutrition. The abbreviation stands for "Middle-Upper-Arm-Circumference". The MUAC test is carried out on children aged between six months and five years. Trained personnel measure the circumference of the left upper arm using a specially developed measuring tape with a color scale.

The particular advantage here is that the bracelet is simple and inexpensive to produce and is quick and easy to apply. The band is placed on the upper arm, in the middle between the elbow and shoulder. The color scale then shows the child's nutritional status at a glance. In addition, the MUAC results are statistically significant indicators in determining the risk of infant mortality. The MUAC test can also be used to quickly examine a large group of children.

The three areas of the MUAC band:

The thresholds for SAM and MAM of the MUAC measurements can vary from country to country as these are adapted on country level.

- Green for an arm circumference of 12.5 cm or more = normal condition; well nourished and low risk of mortality.

- Yellow for an arm circumference of 11 cm to 12.5 cm = moderate acute malnutrition; risk of rapid deterioration in nutritional status and treatment recommendation.

- Red for an arm circumference of less than 11 cm = acute malnutrition; in need of medical and nutritional support.

Infants between the ages of six months and five years are among the most vulnerable groups and therefore a reflection of the whole society. However, the MUAC test can also be a reliable indicator for pregnant women that the baby's birth weight is too low. In order to properly support expectant mothers during pregnancy, Malteser International focuses on monitoring the nutritional status of women. This not only helps mothers to survive pregnancy and birth, but also has a positive impact on the child's development.

Causes of malnutrition in children

The most common causes of hunger and malnutrition include poverty, wars and natural disasters. The latter are exacerbated by climate change, contributing to the loss of crops, livestock or income opportunities due to extreme weather events such as droughts or floods, and leaving them without food.

The risk of malnutrition already starts in the womb. The mother's nutritional status has a significant influence on the development of the unborn child. Malnutrition during pregnancy usually results in children being born underweight and with a weakened immune system. The affected children are therefore more at risk of dying in infancy. The effects of early malnutrition are also noticeable later in life - these children are often delayed in their development and more susceptible to illness.

Health consequences of malnutrition in children

While well-nourished children have enough energy to grow, play and learn, undernourished children are usually too small and too light for their age or size. The effects can be seen in various symptoms: they are often weak, tired and lethargic. In many cases, the stunting or wasting of children leads to delayed mental development and even cognitive disability.

Undernutrition is also noticeable in children in the form of physical wasting due to a lack of fat, protein, vitamins, trace elements and minerals. This is also accompanied by a weakening of the immune system, which makes the child more vulnerable to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis. In addition to the risk of illness, there is also an increased risk of mortality.

Why the first 1,000 days are crucial

The first 1,000 days of a person's life - measured from conception to the child's second birthday - are a critical time window. The food consumed during this time has a direct influence on the holistic development of the child. Its immune system, metabolism, digestive system, hormonal balance and brain development can be both negatively and positively influenced by nutrition. The influence on the unborn child in the womb is therefore also known as "fetal programming". Certain risk factors during pregnancy, such as malnutrition, but also maternal obesity, smoking and alcohol consumption, eating raw meat or excessive coffee consumption, increase the likelihood that the child itself will later become underweight or overweight or suffer from cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary food for moderately and acutely malnourished children

If the MUAC test is in the yellow zone or if the children only weigh around 70-80% of the normal weight, they are considered to be moderately undernourished. This is already a critical health status. Preventive measures are required to ensure that the nutritional status does not deteriorate further and the MUAC test slips into the red zone. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, moderately undernourished people are given "mélange mais-soya", a corn soy blend (CSB), which is served as porridge. The advantage here is that the food can be produced locally. Malteser International can thus make an effective contribution to treating cases of moderate acute malnutrition and preventing a deterioration towards severe acute malnutrition.

The red area of the MUAC band signals severe acute malnutrition (also known as wasting). If children in this condition are not treated properly, the risk of death increases. This is where the "Community-Based Management of Acute Malnutrition" (CMAM) model was developed. This approach enables community members to treat acutely malnourished children at home and refer them to a local health facility if necessary.

The CMAM approach consists of four basic principles:

- Improved access to treatment in communities: The CMAM program creates the opportunity to provide wasting treatment in close proximity to the affected communities.

- Fast action: The signs of acute malnutrition (or wasting) should be recognized as early as possible, before complications arise, so that the majority of acute malnourished children can be treated at home.

- Needs-based care: With the help of CMAM, care is tailored to the individual needs of the child. As a result, only the most severe and complicated of acute malnutrition cases require inpatient hospital treatment.

- Long-term care: By integrating CMAM services into the local healthcare system, a longterm treatment routine should be made possible.

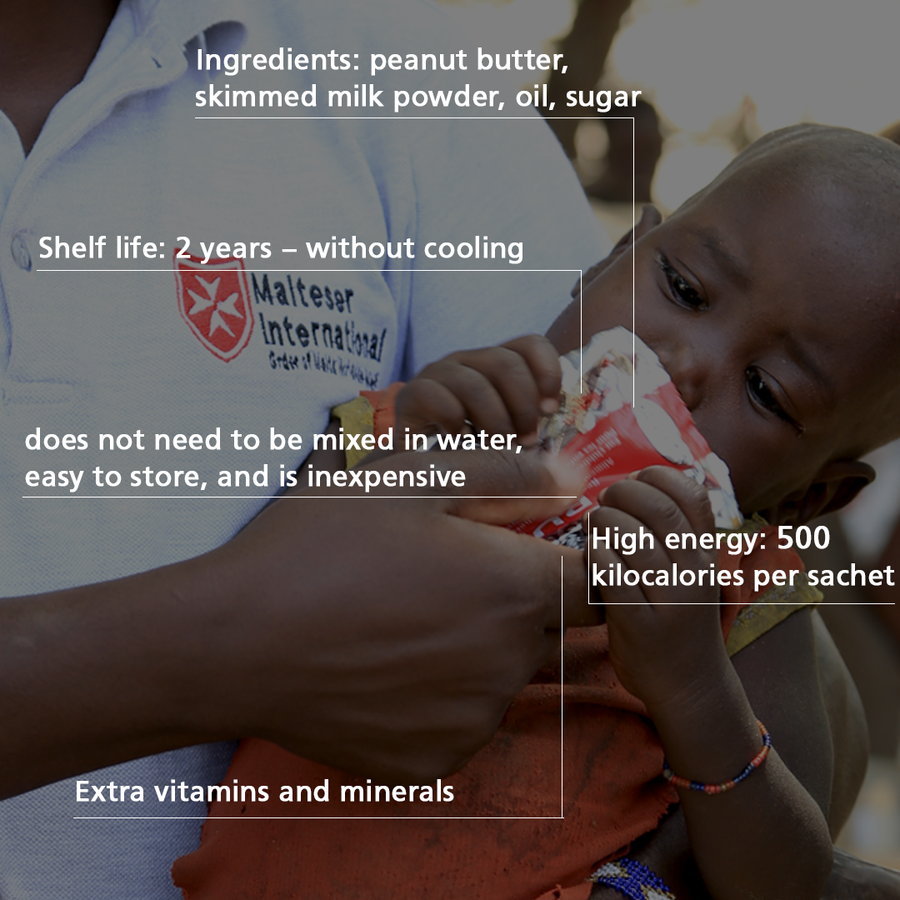

In cases of wasting, peanut paste is very suitable as a supplementary food - also known under the brand name "Plumpy Nut". The paste consists of peanut butter, oil, milk powder and sugar. It also contains essential vitamins and minerals. The peanut paste is ready to use and does not need to be mixed with water. As such, the consumption of Plumpy Nut poses a low hygienic risk of diarrhea, which would further worsen the children's nutritional status. Another advantage of the paste is that it can be purchased very affordably or even made yourself. The cost of treatment for a child is only around 5 euros per month.

How we treat children with acute malnutrition

The treatment of acutely malnourished or undernourished children follows a 10-point scheme developed by the World Health Organization (WHO).

- Treatment and prevention of low blood sugar with glucose: Glucose can be administered orally or intravenously.

- Treatment of hypothermia and monitoring of body temperature: Hypothermia (body temperature below 35 degrees Celsius) can easily be counteracted with blankets or heaters. Body temperature should be measured and recorded regularly.

- Treatment of dehydration: Special solutions for rehydration (ReSoMal) are best suited. Care must be taken not to overload the circulation. Close monitoring of pulse and respiratory rate is therefore recommended.

- Monitoring the electrolyte level: The aim is to bring it back into balance. This can be achieved primarily by administering liquid potassium and magnesium.

- Administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic: As infections can occur without symptoms due to the weakened immune system, patients are given a broad-spectrum antibiotic as a precaution. In addition, children over the age of six months are vaccinated against measles if their condition is stable.

- Supplementation of vitamins and trace elements: Vitamin A, zinc, folic acid and iron are particularly important.

- Administration of supplementary food: The feeding of additional food should be started carefully at first so as not to overload the weakened body. Small, but several portions are given, which should contain around 100 kcal per kilogram of body weight in children. In addition, enough liquid (100-130 ml per kilogram of body weight) should be given.

- Monitoring the growth: The weight increase should be monitored at regular intervals and ideally be around 10 grams per kilogram of body weight within a day.

- Create a positive and encouraging environment: As malnutrition often causes a delay in mental development, it is important to provide a supportive and protective environment. Where possible, caregivers should be involved in the treatment.

- Monitoring and regular check-ups: This should involve the child's parents or caregivers, who will ensure that the follow-up appointments are kept.

Our measures to prevent malnutrition in children

There are many ways to prevent malnutrition in children, starting with the mother's diet during pregnancy. In our health centers, we offer comprehensive care for expectant mothers and their babies during and after pregnancy.

As part of antenatal care, we are committed to raising awareness among expectant mothers about proper nutrition. This includes an increased calorie requirement from the second and third trimester of pregnancy, for instance. In the second trimester, the requirement is already around 250 kcal higher than normal, and from the third trimester onwards it is another 250 kcal more. Accordingly, mothers need to eat more food to cover their higher energy requirements.

In risk areas, malaria prophylaxis is also advisable, as the infectious disease can be dangerous for the mother and unborn child even in the early stages of pregnancy. Prophylaxis can be carried out by regularly taking the appropriate medication, strictly weighing up the benefits and risks.

The early initiation of breastfeeding is an important step in providing the newborn with colostrum (the mother's first milk) and thus preventing infections and infant mortality. In addition, immediate breastfeeding promotes the emotional bond between mother and baby and forms the basis for exclusive breastfeeding over the next few months.

It is also essential to educate families about healthy and child-friendly nutrition during postnatal care. In the first six months, exclusive breastfeeding with breast milk is considered the best nutrition for the child's development, if this is possible. This is because it provides the child with an optimal supply of all the important nutrients. Milk substitutes, on the other hand, cannot replace breast milk, but rather pose a potential risk of contamination and life-threatening diseases, especially in crisis areas. The benefits of breastfeeding are not limited to the babies - mothers also benefit from it. For example, breastfeeding promotes the involution of the uterus. Moreover, breastfeeding mothers have a lower risk of breast and ovarian cancer in the long term.

The mother's diet is also important during this time. Instead of food that is rich in carbohydrates and low in vitamins, the diet should focus on cereals (such as rice or millet), vegetables and fruit. In our nutrition courses and workshops, mothers and fathers can learn and exchange information on the basics of healthy nutrition for themselves and their infants in order to prevent all forms of malnutrition.

The WHO recommends starting to diversify a baby's diet from around six months of age. This means that other solid and liquid foods are gradually introduced into the diet, as breast milk alone no longer meets the baby's nutritional requirements from this age. Ideally, breast milk remains an important nutritional component until the child is two years old and is supplemented with complementary foods. Gradual food diversification through complementary foods is an important step for the child's development and aims to provide the baby with a balanced diet that meets energy requirements during this important developmental phase and also introduces new tastes, smells, textures and colors at an early age.

In addition to these measures, we support many countries not only with nutrition courses, but also provide trainings. In the area of sustainable agriculture, for instance, we're teaching communities how to improve the food situation in the long term. We also distribute seeds or agricultural equipment to enable a more diverse and fruitful harvest.