This time, it's also the loss of culture

After the severe earthquake in August 2021: An interview with Yolette Etienne, Program Coordinator at MI in Haiti.

earthquakes in Haiti. Photo: Danie Duval

On August 14, 2021, another massive earthquake struck the Caribbean nation of Haiti. The MI team, which has been working with local partner organizations in Haiti since 2010, was on the ground to help in the crisis region in the very first days. Yolette Etienne has now lived and worked through both of Haiti’s most violent and damaging earthquakes in recent history. And still, “tragedy”, “misfortune” and “catastrophe”, are not words you will find in her lexicon. Driven by deeply personal experiences, she has channeled them into her work as a humanitarian expert, and now as MI Americas’ Country Coordinator in Haiti. Sara Villoresi, Communications Officer at MI Americas in New York spoke with her about humanitarian aid in Haiti and her personal experiences.

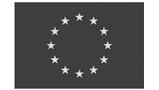

Villoresi: The department of Nippes, where MI has been working for many years, was particularly hard hit by the earthquake in August 2021. How was MI able to help?

Etienne: In particular, many medical facilities had been destroyed and there were many injured. Therefore, in the first emergency phase, we initially provided this working medical facilities with consumables and medicines and supported particularly needy people such as women, elderly people and people with disabilities with the distribution of water, food, protective tarpaulins and cash.

We then focused more on education, access to clean drinking water, continued support for medical centers and cash distributions, and comprehensive psychological support for people in affected rural areas and school children. We have already been able to organize psychosocial activities for more than 4,000 students and teachers in 26 schools in three districts. In the communities, we have been able to reach more than 40,000 people with our services. In the meantime, almost half of the destroyed or damaged schools have been rebuilt, and children in the affected areas can go back to school.

Villoresi: You were in Haiti during the 2010 earthquake. How is this earthquake different?

Yes, I was here. The main difference is location: in 2010, Port-au-Prince (Haiti’s capital) was the epicenter, now the epicenter was in the rural areas in the south. The size, impact, and loss of life in 2010 was enormous, we were all overwhelmed at the national and international level. We didn’t know where to start.

This time, it’s not only about human loss, it’s also about cultural loss. Many churches and monuments of our patrimony were lost. Beyond their symbolic and spiritual importance for the population, these could have generated income through tourism, but now, all of this is lost.

In 2010, there was a feeling of invasion of international organizations. Everyone was doing whatever they wanted, completely marginalizing the population of Haiti, the government of Haiti, and local organizations. Now, there seems to be a change, at least in how we discuss aid in Haiti. We seem to have understood that it’s better to leave space for local organizations. However, these coordination efforts are already waning again, and we must continue to work on this.

Our help in Haiti

5 health stations were supported by MI with material and medicine.

10,000 people were able to improve their livelihoods in the long term through projects like vegetable gardens or orchards, sheep or goat breeding.

3,600 needy people, especially pregnant women, nursing mothers, elderly people and people with disabilities received emergency aid in the form of cash distributions.

Villoresi: As you mention, there has been much criticism about the way aid has been handled in Haiti. Are cash distributions – a rising trend in humanitarian aid – the best way to get aid directly to the Haitian people?

For me, cash, in and of itself, is not a solution. But cash as a component of good programming is a dignified way to aid the people whom we serve. It also makes economic sense. If we accompany people and show them how to invest this cash to make it work for them in a sustainable way, we can help them regain their livelihoods, which is fundamentally why we’re here.

The first cash distribution we did in the earthquake’s immediate aftermath was symbolic in quantity. But it showed the population that we trust them to know what they, as individuals, need better than we do. It also makes economic sense for Haitian markets, many of which (in Les Cayes, Jérémie, and Miragoane) remained intact. By giving them limited cash instead of large food distributions, we are sustaining these local markets.

The important thing is transparency, access, and accountability. From the very beginning, we made sure everyone was aware of the criteria we were using to distribute aid: that we were going to focus on women, the elderly, and those with disabilities. Another difference is that we’re bringing the cash to them. Many NGOs will set up their distributions in larger cities, making it more difficult and dangerous for those who live in rural areas to access this aid. When we localize, we work with the local authorities who give us the list of recipients in their municipality. But while we respect them and their knowledge, we’re also aware of how rampant corruption is at this level. To increase accountability, we’re the ones distributing the cash with our local partners AHAAMES, and we make sure all the criteria are respected. We’ve also built relationships with the local population over many years, we know their situations.

Villoresi: I imagine the insecurity in Haiti has an impact on humanitarian efforts overall. How has it affected our work particularly regarding cash distributions?

The short answer is yes, it’s certainly an issue, and we need to step up our security efforts. We do this, for example, by working more in home offices to minimize commutes, or by using humanitarian flights instead of traveling overland to avoid gang-controlled areas.

Gangs have the power to limit our movement, they attack convoys and aid workers. Our general feeling is that the government and the police are not in control of this insecurity, so we cannot rely on them for assistance. While gang violence is normally concentrated in urban areas, we’ve witnessed a rise in insecurity in rural areas, which is a concerning trend. A lot of cash has been distributed in the most affected regions, which has created a positive dynamic. Unfortunately, exchanges with the capital are more or less blocked due to the difficult security situation, which significantly reduces the positive effects.

Villoresi: To close, I wanted to touch on something more personal. In the early days of the emergency, our team had created an internal group chat to coordinate our efforts and share information. At one point, Yolette mentioned that one of the 2,200 casualties of the earthquake was one of her dearest friends, a priest named Emile Beldor. In the heat of things, we quickly moved onto logistical and security tasks, but I hadn’t forgotten about that message and wanted to follow up. This is your home, these are your friends, your family. How are you coping?

It was the same thing in 2010. In 2010, I lost my mother in the earthquake, as well as kids I considered my own. It was very painful, and the only way I found to overcome such things was by supporting others. If you don’t have that, I don’t think you can deal with this kind of situation, and it’s the same thing now. The friend I lost in this most recent earthquake was a friend I’d known for over 40 years. He was a priest, completely dedicated to the population. And if he was alive, he would have been the first to support hundreds, thousands of people, too. That’s also it, every single life is important. I could not attend his funeral because I need to do my job. It’s the best way to honor him. That’s why I thank MI and appreciate the type of work I do: I get to put all my energy into ensuring we are doing this right.

Our Worldwide Emergency Response in 2021

We help people in need during crises such as natural disasters, epidemics or armed conflicts. In 2021, we provided aid in more than 20 emergencies:

| + Emergency aid for refugees in Afghanistan, Iraq, Colombia, Syria, Uganda, and the Central African Republic. |

| + Emergency aid following floods in Bangladesh and South Sudan |

| + Covid-19 emergency aid in the DR Congo, Kenya, Colombia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Nepal, India, and Venezuela. |

| + Emergency aid following Typhoon Rai in the Philippines and the Hurricanes ETA and IOTA in Guatemala. |